It is in our natures to serve our personal interests first and those of others second. The interests of others include not only those around us in need but also our children and future generations in general, which are served by far sighted policies that might entail short-run and immediate sacrifices. Communities and societies that have instilled in each generation the values that promote and serve such longer-run interests will flourish relative to those with more narrowly “selfish” values.

Adam Smith famously explained in The Wealth of Nations how an individual’s pursuit of his personal gain benefits society at large. In the marketplace the fruits of our labors enjoy the greatest profit the better they meet the desires and needs of our customers at the lowest possible cost. While we might like to cut corners and raise our prices if we could get away with it, competition in the market prevents us from doing so.

Free trade and the international agreements that promote it is an example of the trade off between personal and community or national interests that I am raising. The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) will further extend the freedom to trade among the countries signing up to them while raising the standards for working conditions, intellectual property protection, and conflict resolution.

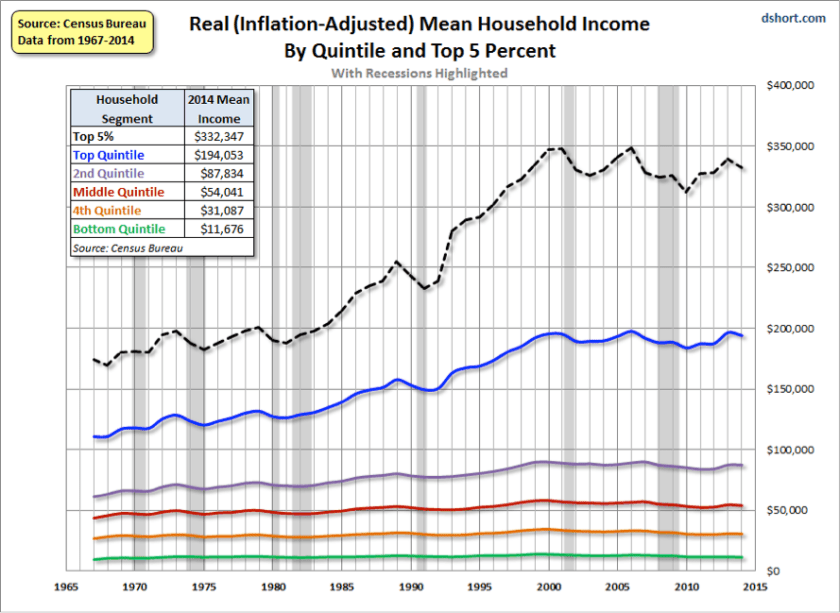

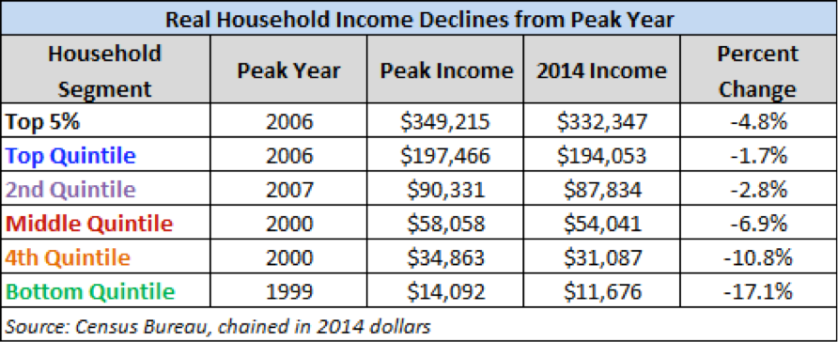

I began an article on free trade written a year and a half ago with: “World per capita income didn’t change much from the time of Christ to the founding of the United States ($444 to $650 in 1990 dollars), a period of 1,790 years. But in the following 320 years it jumped to $8,080. And about half of that jump came over the last 50 years. What explains this fairly recent explosion of well being? Many things, of course, but central to this explosion of wealth was trade.” free-markets-uber-alles As the most disheartening and distressing U.S. presidential campaign in my lifetime has made clear, the huge gains from freer trade as with the huge gains from technical advances have not been evenly shared thus highlighting the trade off between personal and community interests I am exploring.

We have long accepted that economic progress should not be stopped because it would make a particular set of skills or tools less valuable. When someone developed cheaper and better ways of providing us with music than the old 78 inch vinyl record—itself an amazing technological feat in its time—those producing the old records were forced to learn new skills. We should debate whether society (family, church, community governments, etc.) should help those adversely affected by technological progress and how best to do it, but few would want to prevent such progress from which almost everyone in the world has eventually benefited enormously.

Government, which represents an exercise of our collective will, is meant in part to give primacy to our concerns for the interests of others and/or the long run over our individual, immediate personal well being. The American constitution was all about trying to do that without the government becoming captive of the self-interest of those running it. Our natures, whether we operate as private individuals constrained by the market place or as public officials constrained by the law and a broadly agreed public purpose, remain a mix of self-interest and public interest. The fundamental difference between our behavior as private citizens or public servants is in the external constraints that impact our behavior. Our natures otherwise remain the same.

The power of government can be exploited to thwart the discipline of competitive markets on the dominance of self-interest over the common interest. Preventing government from being captured by the self-interest of those running it or those who seek special privileges from it is no easy task. To that end our constitution strictly limited what government could do (the enumerated powers) and encumbered it with checks and balances. The dangers of such capture posed by the military industrial complex of which President Eisenhower warned, is well known and real (e.g. $400 billion F-35 Joint Strike Fighter that few believe we need), but the same is true of most other intrusions of government into private affairs, such as all of our many wars (on drugs, terror, poverty, etc.) as well.

Sadly our government has expanded well beyond its necessary functions into every nook and cranny of our personal lives with increasingly pernicious and alarming results. The abuses of its ever-expanding powers for personal and partisan benefits are exemplified by the scandal of asset forfeiture,the-abuse-of-civil-forfeiture/, which alarmingly continues, the long and bipartisan history of political abuse of the IRS, irs-tea-party-political, and most recently the legal attack on companies questioning the climate change forecasts of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) by the AGs United for Clean Power using the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act in an effort to silence criticisms of UN climate studies. prosecuting-climate-chaos-skeptics-with-rico. Such a blatant government attack on free speech is truly shocking. These are but a few examples of growing government tyranny and corruption.

The most effective defenses against such corruption are to limit the scope of government as much as possible (i.e. subject individual actions to the discipline of the market as much as possible) and to strengthen public insistence on adherence to the rule of generally applicable law. As trade has moved beyond the village and nation, so must the rule of law.

Following World War II the United States led the establishment of international arrangements and laws governing trade (WTO) and financial (IMF and WB) and diplomatic (UN, NATO) relations among nations. The U.S. was the natural leader of this globalized world not only because it had the largest economy and the largest military, but because it was generally respected for its commitment to the rule of law. More than any other country the U.S. was seen as committed to the longer run prosperity of the world above short run tactical benefits for itself.

In an April 12, 2016 interview by Steve Clemons in The Atlantic, U.S. Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew observed that “In the 21st century, the world needs the United States to be a North Star. The world wants us to be the North Star. I really do believe that. I am amazed at how other countries want to hear our advice and what we think makes sense. Sometimes we may have the habit of lecturing too much. We have to be careful not to do that.”

In recent years American leadership has been slipping. Rather than draw China more tightly into the global rule based trading system, we have pushed them away. After the United States convinced the IMF’s European members to accept a reduction in their share of votes in the IMF in order to bring the voting shares of China, India, and some other emerging economies more in line with their economic size, it took the U.S. Congress more than five years before it approved the amendments to the IMF Articles of Agreement needed to implement this agreement. In the mean time China set up its own international lending organization. US-leadership-and-the-Asian-Infrastructure-Investment-Bank

Rather than strengthen cooperative, diplomacy based relationships the U.S. has launched a series of generally failed wars to promote “democracy,” (Gulf War 1990-91, Somalia 1992-5, Haiti 1994-5, Bosnia 1994-5, Kosovo 1998-99, Afghanistan 2001 – to date, Iraq 2003-11, Libya 2011). These have weakened respect for American leadership.

On the economic front the United States has imposed hugely costly anti-money laundering (AML) and global tax reporting (FACTA) requirements on the rest of the world without regard for their cost and despite the lack of any evidence of benefits. Operation Choke Point These are serious abuses of American leadership that will produce a growing backlash. But it is not just misguided arrogance that is undermining our role in the world, it is the growing perception that our leadership is increasingly motivated by the selfish personal interests of crony capitalists rather than the high principles that have serviced us and world so well in the past.

Consider the example of the FATCA (Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act). Badly designed corporate and income tax laws in the United States have pushed an increasing number of companies and wealthy people out of the U.S. Rather than clean up its tax laws, the U.S. attempts to tax the income of Americans where ever they earn it and where ever they might live. The only escape is to renounce U.S. citizenship. The Obama administration is now proposing an exit wealth tax for American’s giving up their citizenship. It reminds me of the measures the Soviet Union took to prevent its citizens from leaving. Have we really fallen so low?

The use of off shore, tax minimizing structures by American companies and individuals (i.e. legal tax planning measures) as well as illegal efforts to hide income have been met by increasingly intrusive efforts by the U.S. to find and tax such income. Quoting from the introduction of the Wikipedia article on FATCA: “The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) is a 2010 United States federal law to enforce the requirement for United States persons including those living outside the U.S. to file yearly reports on their non-U.S. financial accounts to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FINCEN). It requires all non-U.S. (foreign) financial institutions (FFI’s) to search their records for indicia indicating U.S. person-status and to report the assets and identities of such persons to the U.S. Department of the Treasury.”

As the world attempts to comply with American extra territorial demands, the United States itself is not. Such reporting requires knowledge of the beneficial owners of companies. Most companies established in the United States, such as those incorporated in Delaware, are not required to provide the identities of beneficial owners. The U.S. seems to have no intention of requiring its companies to comply with what it demands from other countries.

The decline and fall of the “American Empire” seems to be underway. It doesn’t need to be.