Philadelphia Society Address on Oct 14, 2017

Introduction

Sound money is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for a healthy economy. How can we best achieve and maintain it?

For almost two hundred years the gold standard did a good job of producing sound money but its weaknesses ultimately led to its abandonment and exchange rates were allowed to float.

The movement in the 1980s to independent central banks with a stable price level mandate, such as an inflation target, delivered several decades of sound money—this was called the great moderation. But is came at the expense of increased exchange rate volatility and asset bubbles.

We need to return to a monetary regime with a hard anchor. But money fixed in price to a single commodity, such as gold, will not provide as stable a value as a price fixed to a larger basket of goods.

The discretion of the central bank to control the supply of money should be replaced with market determination of the money supply. To achieve this money should be issued under currency board rules. Specifically the public should be able to buy all of the currency they want at the currency’s official prices and redeem any of it they no longer want at the same price.

The Gold Standard

The essence of the gold standard was the obligation of the issuer of gold backed money to redeem it for gold at an officially fixed price. This limited the amount of money that could be issued. The United States set the price of fine gold at $19.49 per ounce in 1791 and raised it to $20.69 in 1834. The Gold Standard Act of 1900 lowered it slightly to $20.67. In 1934, Congress passed the Gold Reserve Act, which raised the price of gold to $35 an ounce and prohibited private ownership of gold in the United States. Lyndon Johnson’s guns and butter deficit spending over heated the U.S. economy, which raised doubts about the U.S.’s ability to honor its gold commitments. By late 1971 the U.S. no longer had enough gold to honor its redemption commitment, and President Richard Nixon suspended the U.S. commitment to buy and sell gold at its official price. Yet, an official price remained, and was raised to $38.00 per ounce in 1971 and to $42.22 in 1972. In 1974, President Ford abolished controls on and freed the price of gold, which rose to a high of $1,895 in September 2011 before falling back to $1,304 this morning (October 14, 2017). More importantly, as gold has never been very representative of prices in general, prices of goods and services on average in the U.S. rose 500% over the 45 years since Nixon closed the gold window.

Floating Exchange Rates and Inflation Targets

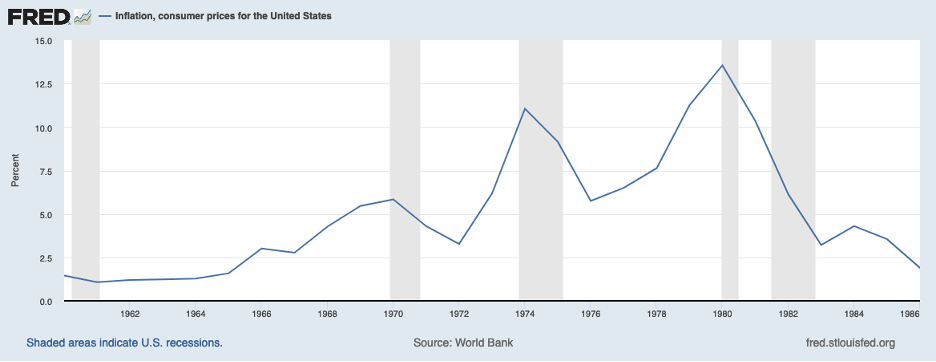

When Nixon closed the gold window he also imposed wage and price controls, which lasted for three years. The dollar no longer had a “hard” anchor. It was no longer redeemable for anything and new policies were needed to regulate its supply. Over this period the Fed implemented monetary policy via adjustments in the overnight interbank lending rate (the Fed funds rate) in light of, among other things, its objectives for the growth of monetary aggregates. When wage and price controls were finally lifted the CPI increased a staggering 12% in 1974.

In the face of the Fed’s persistent over shooting of its narrow and broad money target ranges and the entrenching of higher and higher inflation expectations in wage and price increases, Federal Reserve Board Chairman Paul Volcker led the Board and the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) on October 6, 1979 in a dramatic change in the Fed’s approach to implementing monetary policy by shifting to an intermediate, narrow money target, operationally implemented via a target for non-borrowed reserves. The new approach required the Fed to relax its Fed funds rate targets and it increased the band set by the FOMC for the Fed funds rate from 0.5% to 4%. However, the fed funds rate rose temporarily to over 22% and GDP fell by over 2% in 1982—actual and expected inflation were reversed and fell below 2.5% by 1983. The new approach had defeated inflation but it was not easy to implement and by the end of 1989 the Fed abandoned it for the more traditional fed funds rate targeting.

At about the same time radical innovations in the development of monetary policy rules were launched by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, which came to be known as explicit inflation targeting. An inflation target provides a clear and explicit rule that permits flexible operational approaches to its achievement. Given Friedman’s long and variable lags in the effect of monetary policy on prices, setting monetary operational targets (almost always the equivalent of a fed funds rate) must be based on the best model assisted forecast of its consistency with the inflation target one to two years in the future. A longer target horizon provided more scope for smoothing any output gap (employment). Full transparency of the policy and the data and reasoning underlying policy settings is required to gain the benefits of the alignment of market inflation expectations with the policy target.

The RBNZ’s development and adoption of inflation targeting was an important development in the pursuit of rule based monetary policy with floating exchange rates that accommodated flexible implementation. It swept the world of central banking. While the Fed did not adopt explicit inflation targets until 2012, it clearly pursued an implicit inflation target long before that.

Monetary stability, defined as price level stability, improved significantly, but exchange rate volatility increased. The Great Moderation of the 1990s and early 2000s that resulted from more stable domestic prices was followed by the Great Recession. The Great Recession of December 2007 to June 2009 highlighted the failure of inflation targeting to take account of asset price bubbles and “inappropriate responses to supply shocks and terms-of trade shocks”.[1]

What followed can only be described as a nightmare (largely because of the over leverage and other weaknesses in the U.S. financial system). After properly and successfully performing its function of a lender of last resort and thus preventing a liquidity-induced collapse of the banking system, the Fed went on to undertake ever more desperate measures to reflate the economy. These Quantitative Easings (QEs)—quasi-fiscal activities—have been widely discussed and have contributed little to economic recovery.[2]

The conclusion from the above history is that monetary policy is being asked to deliver more than it is capable of delivering. Central banks are generally staffed by very capable people, but they can never know all that they need to know to keep the economy at full employment as employers and jobs keep changing. The quality of forecasting models has greatly improved in recent years, but they remain unreliable. The policy strategy and intentions of the Fed and other inflation targeting central banks have become admirably transparent, but given the uncertainty of its next policy actions, markets remain spooked by every new data release and speech by Fed officials. Yet inflation in the U.S. and Europe remain below the 2% targets of the Fed and of the ECB.

Despite the huge increase in the Fed’s balance sheet, which banks are largely holding as excess reserves at the Fed, monetary growth in the U.S. averaged only about 5.5 to 6% over the past four years or about the same as its long run average (for M2). My assessment of the slow pace and modest size of the economic recovery in the U.S. is that regulatory burdens have discouraged investment while many internet related investments continue to drive down costs of many economic activity (a sort of unrecorded productivity increase). Easy money is once again inflating asset prices (stocks and to a lesser extend again real estate). But who knows for sure?

The idea that central banks can micro-manage monetary conditions to smooth business cycles is a conceit. In my opinion, central banks have given their price stability mandates their best shot and failed. The successful, countercyclical management of the money supply with floating exchange rates is simply beyond the capacity of mortals.

Return to a Hard Anchor

The Fed should give up its management of the money supply and return to a system of money redeemable for something of fixed value – a so-called hard anchor for monetary policy. This means linking the value of money to something real and managing its supply consistent with that value (exchange rate). Such regimes do not magically overcome an economy’s many and continuous resource allocation and coordination challenges, but by providing a stable unit in which to value goods and services and to evaluate investment options, and sufficient liquidity with which to transact, such regimes facilitate the continuous adjustments private actors need to make for an economy to remain fully employed and to grow.

But fixed exchange rate regimes, including the gold standard in one of its forms or another, have historically had their problems as well. These problems generally reflected one or the other of two factors. The first was the failure of the monetary authorities to play by the rules of a hard anchor, which is to keep the supply of money at the level demanded by the public at money’s fixed value. The pressure to depart from the rules of fixed exchange rates generally came from fiscal imbalances or mistaken Keynesian notions of aggregate demand management. However, even when central banks aimed actively to match the supply of its currency to the market’s demand with stable prices it proved beyond their capacity to do so.

The second source of failure came from fixing the value of money to an inappropriate anchor. When the exchange rate of a currency is fixed to another currency or to a commodity whose value changes in ways that are inappropriate for the economy, domestic price adjustments can become difficult and disruptive. Fixing the exchange rate to a single commodity, as with the gold standard, transmitted changes in the relative price of gold to prices in general, which imposed costly adjustments on the public.

These historical weaknesses of monetary regimes with hard anchors can be overcome by choosing better anchors and by replacing central bank management of the money supply with market control via currency board rules.

Currency board rules give control of the money supply to the market—to the public. As an example, a strict gold standard operated under currency board rules would increase the money supply whenever the public wanted more and was willing to buy it with gold at the fixed gold price of a dollar. If the public found it held more money than it wanted it would redeem the excess for gold at the same price.

I led the IMF teams that established the Central Bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina with currency board rules, and it functions in exactly this way. It has no monetary policy other than issuing or redeeming its currency for Euro at a fixed exchange rate in passive response to market demand. It has worked very well. I was also involved in establishing currency board rules for the Central Bank of Bulgaria, which has also enjoyed stable money ever since.

The hard anchor should not be just one thing. The relative price of any individual good or commodity will vary relative to prices in general. Thus a small representative basket of goods should be chosen for the anchor. Earlier proposals for broader baskets suffered from the assumption that buying and redeeming the currency should be against all of the items in the basket. That would be cumbersome and storage and security would be costly. Currency board rules should provide for indirect redeemability, by which the currency would be purchased with or redeemed for designated AAA securities (e.g., U.S. Treasury bills) at their current market value.

Exchange Rate Volatility or a Global Currency

A major cost of the current system of floating exchange rates with inflation or other targets is the uncertainly and wide swings of exchange rates. Over the last decade the USD/Euro exchange rate varied over 40 percent. The classical gold standard was associated with a flourishing of foreign trade in part because the gold standard was a world currency, which there for eliminated exchange rate risk. There would be considerable benefit to world trade, economic efficiency, and growth if all or most countries adopted the same hard anchor for their currencies. The International Monetary Fund’s SDR already exists for this purpose but would need to be modified in several important ways in order to operate under currency board rules and to change its valuation basket from a basket of currencies to a basket of goods.

Conclusion

Experience with monetary regimes with floating exchange rates has been mixed. Almost all major currencies have become more stable in the last three decades but at the expense of increased exchange rate and asset price volatility. The United State, as well as most other countries, would benefit from a return to a monetary system with a hard anchor, but fixed to the value of a small basket of goods rather than to just one, and whose supply is determined by the public’s demand via issuing and redeeming it indirectly for a liquid asset of comparable value according to currency board rules. The benefits of such a system would be increased the more widely it was adopted. One of the virtues of the gold standard was that it was global.

Reference

Warren Coats, “Real SDR Currency Board”, Central Banking Journal XXII.2 (2011), also available at http://works.bepress.com/warren_coats/25

________________, “What’s Wrong with the International Monetary System and How to Fix it?” April 20, 2017. https://works.bepress.com/warren_coats/38/

Jeffrey Frankel. “The Death of Inflation Targeting”. Project Syndicate, May 16, 2012.

_____________________________________________

[1] Jeffrey Frankel. “The Death of Inflation Targeting”. Project Syndicate, May 16, 2012.

[2] See for example, Warren Coats, “US Monetary Policy–QE3” Cayman Financial Review January 2013.